In her Sin muertos, Alicia Giménez-Bartlett has told the story of her best-known character. It’s a way to reaffirm the need to reflect on one’s own actions..

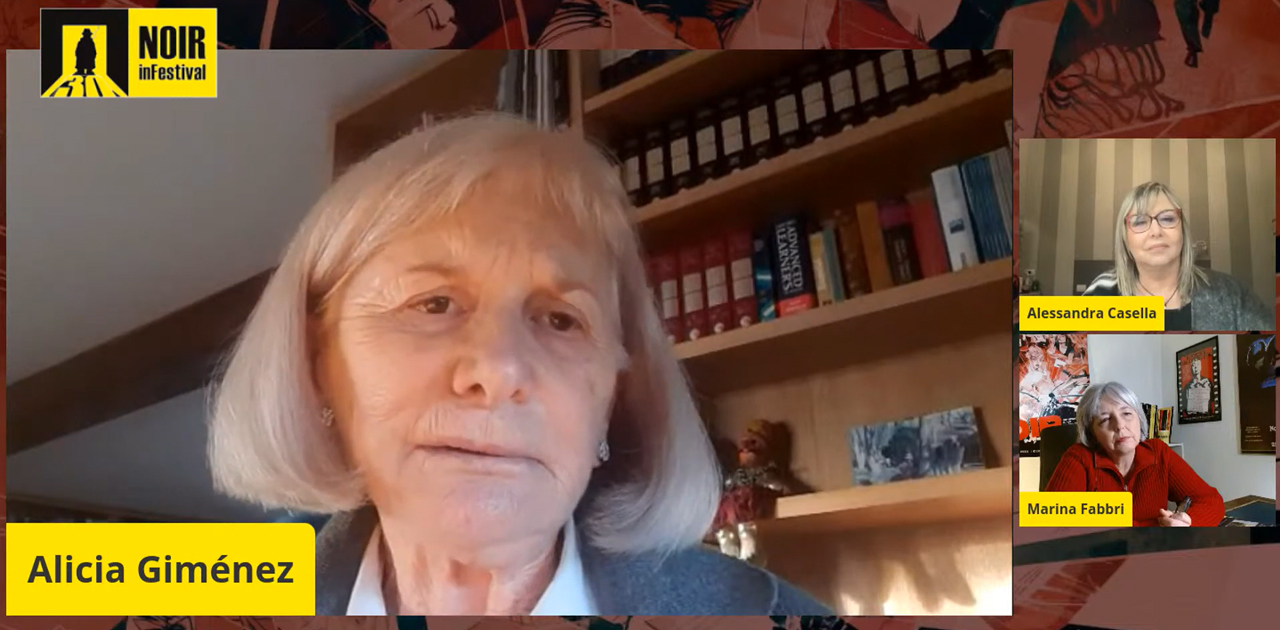

“Did you decide to write the story of this character out of your own intellectual curiosity, or did you want to give your many readers a treat?” With this question, Marina Fabbri kicked off the talk with the Spanish author Alicia Giménez-Bartlett, winner of the Raymond Chandler Award in 2008, here at Noir in Festival with a new book in which the now-renowned detective Petra Delicado investigates herself – that is, writes her own autobiography.

“Well, on the one hand,” replied Alicia Giménez-Bartlett, “Petra has her own personality and personal style, so I wondered how she had come to be that way, what kind of life she’d led. On the other, Petra’s “friends”, or fans, are a multitude, and they follow her every adventure, so, yes, I thought that receiving the Sin muertos would be a wonderful present from me. A present not at all easy to pull off, since I knew nothing about Petra, or should I say, all I knew were her investigations, the fact she’d been married three times and had a more or less normal life. I wanted to do something more concrete in this book, in line with her own way of handling things, but that was hard. A police investigation, with Petra acting more than thinking, is easier. In this novel Petra ponders, tells her story, questions herself about her own life. And by the end, her author was…well, worn out by the effort.”

“We should make one thing clear,” explained Alessandra Casella, brought in to dialogue with Giménez-Bartlett, “and that is, if you’ve never read one novel featuring Petra Delicado, it isn’t a problem. Because this autobiography is actually a stand-alone. It’s the story of a woman who thinks hard about herself: a woman born in the 1950s, and a life lived right up to the present day.”

“At times,” Giménez-Bartlett went on, commenting on the importance of writing an autobiography, “we let our lives rush by without pausing to really think about what we have accomplished. We women especially are prone to helping others, at home, at work, thinking too much about the next person, not ourselves. We are more empathetic than men are. All good, all significant, but at the same time, it makes it much harder to take charge of your own life. We should be saying, ‘I am myself. I have children, husbands, friends, but I’m myself.’ With the power to make decisions, do things, and ask ourselves, afterwards, why we did those things.”

“What about Petra?” Casella asked. “Would she have authorized this autobiography? “Petra is an individualist,” Giménez-Bartlett replied. “She doesn’t trust anyone. She would have said, ‘No, this is my personal story. I won’t give you permission to write it!’ Definitely.” Luckily for us, the author did not ask her famous character to authorize the book.